As part of our continuing effort to improve the performance of twitter.com, we’ve recently implemented pushState. With this change, users experience a perceivable decrease in latency when navigating between sections of twitter.com; in some cases near zero latency, as we’re now caching responses on the client.

This post provides an overview of the pushState API, a summary of our implementation, and details some of the pitfalls and gotchas we experienced along the way.

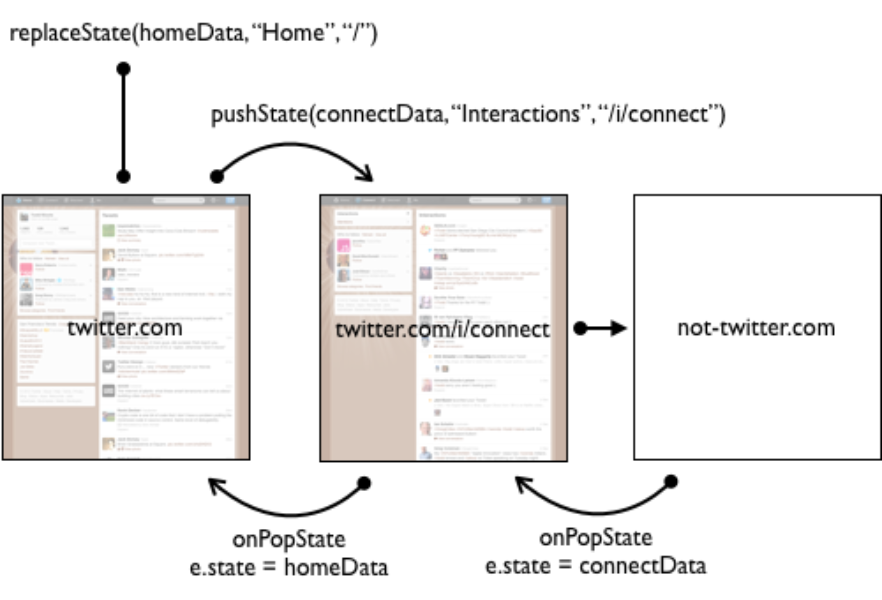

pushState is part of the HTML 5 History API— a set of tools for managing state on the client. The pushState() method enables mapping of a state object to a URL. The address bar is updated to match the specified URL without actually loading the page.

history.pushState([page data], [page title], [page URL])

While the pushState() method is used when navigating forward from A to B, the History API also provides a “popstate” event—used to mange back/forward button navigation. The event’s “state” property maps to the data passed as the first argument to pushState().

If the user presses the back button to return to the initial point from which he/she first navigated via pushState, the “state” property of the “popstate” event will be undefined. To set the state for the initial, full-page load use the replaceState() method. It accepts the same arguments as the pushState() method.

history.replaceState([page data], [page title], [page URL])

The following diagram illustrates how usage of the History API comes together.

Our pushState implementation is a progressive enhancement on top of our previous work, and could be described as Hijax + server-side rendering. By maintaining view logic on the server, we keep the client light, and maintain support for browsers that don’t support pushState with the same URLs. This approach provides the additional benefit of enabling us to disable pushState at any time without jeopardizing any functionality.

On the server, we configured each endpoint to return either full-page responses, or a JSON payload containing a partial, server-side rendered view, along with its corresponding JavaScript components. The decision of what response to send is determined by checking the Accept header and looking for “application/json.”

The same views are used to render both types of requests; to support pushState the views format the pieces used for the full-page responses into JSON.

Here are two example responses for the Interactions page to illustrate the point:

{

// Server-rendered HTML for the view

page: "…

",

// Path to the JavaScript module for the associated view

module: "app/pages/connect/interactions",

// Initialization data for the current view

init_data: {…},

title: "Twitter / Interactions"

}

<b>{{title}}</b>{{page}}

Several aspects of our existing client architecture made it particularly easy to enhance twitter.com with pushState.

By contract, our components attach themselves to a single DOM node, listen to events via delegation, fire events on the DOM, and those events are broadcast to other components via DOM event bubbling. This allows our components to be even more loosely coupled—a component doesn’t need a reference to another component in order to listen for its events.

Secondly, all of our components are defined using AMD, enabling the client to make decisions about what components to load.

With this client architecture we implemented pushState by adding two components: one responsible for managing the UI, the other data. Both are attached to the document, listen for events across the entire page, and broadcast events available to all components.

It’ll come as no surprise to any experienced frontend engineers that the majority of the problems and annoyances with implementing pushState stem from either 1) inconsistencies in browser implementations of the HTML 5 History API, or 2) having to replicate behaviors or functionality you would otherwise get for free with full-page reloads.

All browsers currently disregard the title attribute passed to the pushState() and replaceState() methods. Any updates to the page title need to be done manually.

At the time of this writing, WebKit (and only WebKit) fires an extraneous popstate event after initial page load. This appears to be a known bug in WebKit, and is easy to work around by ignoring popstate events if the “state” property is undefined.

Firefox imposes 640KB character limit on the serialized state object passed to pushState(), and will throw an exception if that limit is exceeded. We hit this limit in the early days of our implementation, and moved to storing state in memory. We limit the size of the serialized JSON we cache on the client per URL, and can adjust that number via a server-owned config.

It’s worth noting that due to the aforementioned popstate bug in WebKit, we pass an empty object as the first argument to pushState() to distinguish WebKit’s extraneous popstate events from those triggered in response to back/forward navigation.

The bulk of the work implementing pushState went into designing a simple client framework that would facilitate caching and provide the right events to enable components to both prepare themselves to be cached, and restore themselves from cache. This was solved through a few simple design decisions:

As is often the case, changing the browser’s default behavior in an effort to make the experience faster or simpler for the end-user typically requires more work on behalf of developers and designers. Here are some pieces of browser functionality that we had to re-implement:

Despite the usual browser inconsistencies and other gotchas, we’re pretty happy with the HTML 5 History API. Our implementation has enabled us to deliver the fast initial page rendering times and robustness we associate with traditional, server-side rendered sites and the lightening quick in-app navigation and state changes associate with client-side rendered web applications.

—Todd Kloots, Engineer, Web Core team (@todd)

Did someone say … cookies?

X and its partners use cookies to provide you with a better, safer and

faster service and to support our business. Some cookies are necessary to use

our services, improve our services, and make sure they work properly.

Show more about your choices.