Nearly three months ago, two bombs shook the Boston marathon, and the world. As news of the blasts and the subsequent manhunt spread, Twitter became a crucial part of the journalist’s toolkit.

Police react in aftermath of explosion #bostonmarathon #boylstonst (John Tlumacki photo) pic.twitter.com/pfgPjcPZAZ

— Boston Globe Sports ( @BGlobeSports) April 15, 2013

The news from Boston dominated conversation on Twitter for the week - although this chart probably underplays the number of tweets on the subject.

For the Boston Globe, (@BostonGlobe) as the biggest local newspaper, it was a time to test its use of Twitter.

The two bombs went off within seconds of each other at 2:48 pm ET on April 15. By 2:57 pm the Globe had tweeted its first, necessarily terse account of events.

BREAKING: A witness reports hearing two loud booms near the Boston Marathon finish line.

— The Boston Globe ( @BostonGlobe) April 15, 2013

This was followed two minutes later with slightly more detail.

BREAKING NEWS: Two powerful explosions detonated in quick succession right next to the Boston Marathon finsh line this afternoon.

— The Boston Globe ( @BostonGlobe) April 15, 2013

When the events occurred, many Globe staff members were actually running in the marathon or covering it, and they immediately snapped into action, live-tweeting the action around them as a way to report from on the ground. The Globe newsroom had a list of its reporters already in place that they used to monitor incoming tweets through TweetDeck. These Tweets were fed into the paper’s live blog of the event, which was the most-visited page on their website after the bombing and during the manhunt. Even when the homepage went down temporarily, staff said they used Twitter as a vital way to share information with readers. But it was a two-way process, with Globe staff harvesting Tweets for nuggets of news they could verify and report too.

And the tweets were coming thick and fast, including this user, who was probably the first person to tweet about the Boston attacks only seconds after the explosions.

Uhh explosions in Boston

— DeLo ( @DeLoBarstool) April 15, 2013

The Globe normally tweets around 40 times a day. Over the next few hours on April 15, they sent over 150 Tweets, including media such as the photograph at the top of this post. That pace was sustained over the next few days as the bomb investigation turned into a manhunt and the Boston area went into lockdown. In the midst of a deluge of information over that week, the Globe remained a credible channel of news, sifting through reports to highlight verified and important information. The Globe used Twitter as a news distribution channel tweeting a lot — and retained and enhanced its credibility. This increased mentions of its content:

And more and more people started to follow the Globe.

Twitter is widely used in newsrooms around the world on a daily basis. The Globe, for instance, has several monitors throughout the newsroom that show a livestream of Tweets from as well as from other local news outlets and Boston-area tweeters. The screens, increasingly common in newsrooms across the country, serve as a visual reference and reminder for the social staff and the wider newsroom of the discussion on Twitter.

This study, produced by Spanish academics in the days after the bombings, showed how the strategy changed the way people retweeted Globe content. Before the bombing, the median retweet per Tweet was between 3 and 5 each. After the bombing, it jumped to 224.

Meanwhile news organizations provided a way for the police in Boston to investigate the case further. When Boston PD tweeted:

Boston Police looking for video of the finish line #tweetfromthebeat via @CherylFiandaca

— Boston Police Dept. ( @Boston_Police) April 15, 2013

It was published on news websites including the New York Times. And Boston’s request for help with finding the suspects was tweeted here:

Do you know these individuals? Contact [email protected] or 1-800-CALL-FBI (1-800-225-5324), prompt #3 pic.twitter.com/QJias1Kywe

— Boston Police Dept. ( @Boston_Police) April 18, 2013

This was retweeted thousands of times. It gave newspapers pictures and facts they could use — with tweets embedded, as they were here.

And finally when the suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was apprehended, of course that was tweeted too.

Suspect in custody. Officers sweeping the area. Stand by for further info.

— Boston Police Dept. ( @Boston_Police) April 20, 2013

As the news swung from the horrific explosions to the manhunt for two brothers, it wasn’t just the mainstream news organizations which adopted Twitter. Seth Mnookin (@sethmnookin), an independent journalist based in Boston with experience working for major national news outlets, knew how to collect observations and report that night and subsequently. The world was hungry for facts from Boston, and Mnookin was one of those who could provide them. As a result of following the manhut in his neighborhood, he saw his followers on Twitter grow from 10,000 to 30,000, as Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales (@Jimmy_Wales) acknowledged:

@sethmnookin When I followed you awhile ago, you had 10,000 followers. Now 30,000. Be late, be right, and be safe.

— Jimmy Wales ( @jimmy_wales) April 19, 2013

With Hong Qu (@hqu), a fellow at Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Mnookin has written one of most comprehensive accounts available of how Twitter was put to use as Boston was locked down and law enforcement agencies combed the city for the suspects, focusing on Watertown. As he notes there, “Twitter coverage of the manhunt in Watertown is a remarkable milestone for journalism.”

Twitter coverage of the manhunt in Watertown is a remarkable milestone for journalism

@hqu

Twitter changed the way Mnookin and many others worked that night. As he observes in the Nieman story, “I had a small reporter’s notebook with me but early on realized that tweeting would be a more effective way to take notes.”

Arrest going on now. “He’s got shit in his pockets. Get down that street now!” pic.twitter.com/rnpWrZ2H2G

— Seth Mnookin ( @sethmnookin) April 19, 2013

He posted pictures, live news, and links as an officer was shot during the manhunt and the net closed around the suspects. He tweeted 483 times between April 15 and 19, including 169 times on April 18, the evening the manhunt came to its conclusion.

That frequency of tweeting the latest aspect of the story meant that more people started following Mnookin to see the news he was reporting.

The pictures were often graphic but the raw information helped shape the story.

Nothing potential about it: blood, body on ground. MT @thetech: Photo from #MIT shooting;warning: potentially graphic pic.twitter.com/bifKr5qOLB

— Seth Mnookin ( @sethmnookin) April 19, 2013

For journalists, Twitter became a prime information source, as Boston-area citizens stayed indoors, tweeting the images outside their windows, and reporters incorporating that information in their stories.

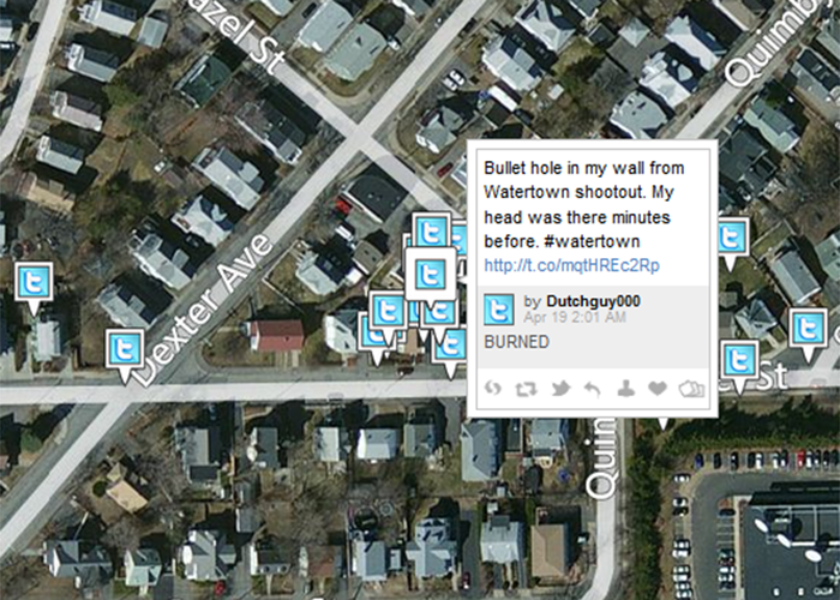

Thanks to Geofeedia, we can show some of the geolocated Tweets around the area as the manhunt was going on.

SWAT coming door to door. About to search my House. #watertown #bostonstrong pic.twitter.com/3dMcXO2BWn

— Barry ( @barrygagne) April 19, 2013

In the aftermath of the investigations, other news organizations found innovative ways to illustrate the story using Twitter data. Business news site Quartz looked at Tweets posted by @J_tsar, the Twitter account reportedly linked to Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, and worked out his sleep patterns based on the timing of his tweets.

Said Mnookin about his experience on Twitter: “The Watertown manhunt illustrated the fact there are times when a traditional journalist can do his job more efficiently and effectively on Twitter than any other medium… for those three or four hours when a gunman was on the loose and a neighborhood was under siege, Twitter was the most efficient way to get information out to the public.”

Mark S. Luckie (@MarkSLuckie), Manager of Journalism and News, contributed to this article

Have you got any stories about using Twitter in reporting? Mail us at [email protected]

Did someone say … cookies?

X and its partners use cookies to provide you with a better, safer and

faster service and to support our business. Some cookies are necessary to use

our services, improve our services, and make sure they work properly.

Show more about your choices.